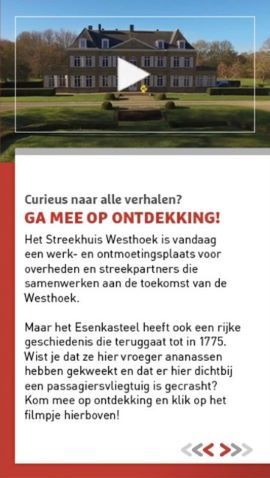

The history of Esen Castle, located on the outskirts of Diksmuide, dates back to 1775. Over time, the castle took on different appearances. Today, from the Esen castle, provincial employees work together with local partners on the development of the Westhoek.

Maurice Maeterlinck

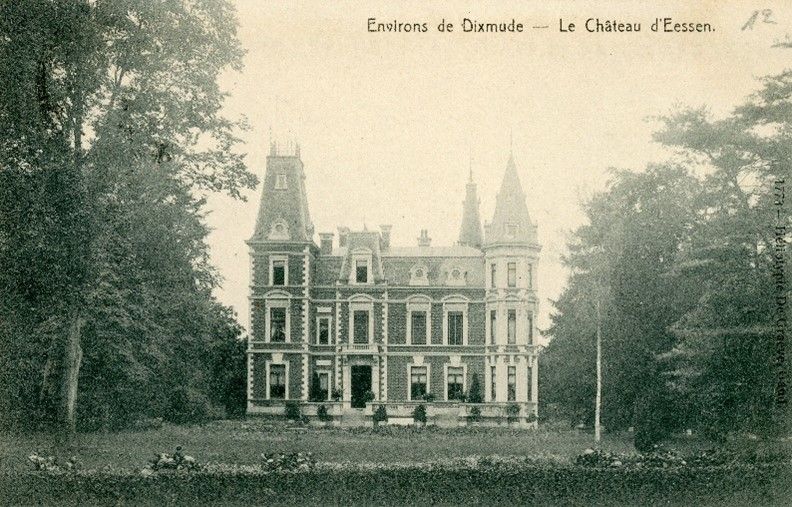

The Ghent playwright Maurice Maeterlinck (1862-1949), son of Polydore Maeterlinck and nephew of Edmond De Ruysscher, entertains us in his autobiography Bulles Blueus (1948) with some lively anecdotes about the goings-on in the late-nineteenth-century Esen castle. In the vernacular at the time, the castle was given the name "Russian Castle," a corruption of the name De Ruysscher, the pharmacist family from Diksmuide who owned the castle at the time. Maeterlinck is not to be found for the nineteenth-century appearance of the castle of Diksmuide:

"The castle of Diksmuide was impressively ugly. It was built on the ruins of a lovely knight's estate from the sixteenth century, of which only an old copper engraving remains as a reminder. The local architect had amalgamated the Tourangeau (Tours region) style with the English rustic building style, crossed with the Swiss country house. To crown the abomination, it had been decorated with stained glass windows of real glass, which looked like transparent chromos, and the sun, accustomed to the beautiful windows of the twelfth, thirteenth and fifteenth centuries, seemed to blush with shame as it lit them up."

The orangery is built in an eclectic brick architecture with battlements and turrets. At the end of the nineteenth century, the castle was given a new look and a chapel was added. It is mainly the eclectic ensemble that is denounced by Maeterlinck. At the beginning of the twentieth century, the castle is named Chateau de la tour blanche, after the tower with white stone ornaments added to the front of the castle.

Uncle Florimond

In odors and colors, Maeterlinck describes his extravagant uncle Florimond, the husband of his mother's sister, who was part of the Diksmuid noble family and spent his summers in the castle.

"He was quite a bit taller than father and made a monumental impression on us. His carefully shaven face looked like an oval full moon. His quadruple chin reached to his stomach and his belly that preceded him by a meter sank to his knees. To make room for his protruding paunch and to make it possible for him to reach the glasses and plates, a wide arched cutout had been made in the tables of his two main dining rooms."

To satisfy his great appetites, a total of four dining rooms are provided in the castle. For parlors, on the other hand, he has an abhorrence. Maeterlinck's lively writing style gives us a picture of what lavish, luxurious life was like in the Esen castle at the time. For example, Uncle Florimond ventures into the cultivation of pineapples, an extremely expensive and daring hobby in the Belgian climate. Indeed, in Northern Europe, the pineapple plant was difficult to pull into bloom. Only extremely rarely did fruits appear on the plant.

"Whenever we were guests of his, which was every two years, he only stood up to show his pineapples. In ilo tempore, he would have said, only a few ventured into this extremely expensive cultivation. For this cultivation from America, he had a special greenhouse built that had to be heated winter and summer with a boiler to a temperature of 25 to 30 degrees. Each pineapple cost him 100 to 150 francs, he admitted. They ripened slowly and laboriously, piece by piece, and the fruit that turned golden yellow received special meticulous care. The rumor of the impending ripeness spread in the region and friends from the neighboring castles, as well as the leading citizens of Diksmuide, came to admire the miraculous fruit."

Polydore Maeterlinck thinks pineapple farming is a waste of money. His melons, he says, are just as tasty, juicier, less pretentious and less destructive. Uncle Florimond dies a year after his successful cultivation. Given his majestic size, his crypt must be widened before his coffin can be lowered into it. After this, the castle residents face uncertain times. The impact of World War I on the castle is incalculable. It is set on fire by the Germans and not rebuilt until 1925. Also during World War II, the castle was occupied by German troops, resulting in damage.

After the war

Maeterlinck writes Bulles Blueus after the end of World War II. He closes the chapter devoted to Uncle Florimond with a melancholy note about the impact of the destructive World Wars on Diksmuide and the castle.

"And all that is no more. The castle, Ypres and Diksmuide were razed to the ground, even the graves disappeared. The two cities were rebuilt, but did the second war, more fierce than the first, respect them? Will it take every twenty or thirty years to start life anew and return to death? And what happened to my sister, a prisoner of the Nazis in Brussels, and Florimond's parents? Is her daughter still alive, and her granddaughter? She was married to a French officer descended from the family of Jacques Amyot, the admirable translator of Plutarchus and Longus and one of the creators of our language. Where are they? No one can tell and I wait with fear in the universal darkness and silence the cruel revelations, the mortal surprises of peace."

On May 6, 1949, a year after writing his Bulles Blueus, Maurice Maeterlinck died at the age of 86.

Practical

Find out more about the special history of the Esen Castle through the Route Streekhuis Westhoek on the ErfgoedApp.